A FORTUITOUS LIFE: JOHN SIDNEY KARLING (1897–1995)

Originally prepared for the Purdue University Herbaria

To hear him speak of his life, John S. Karling was a man plagued by accidents. Every step forward was because of a mistake; every success, because of an error. The modesty he exuded when discussing his accomplishments, and his deference to compliments, illustrate his humble plain-spokenness. One would not expect this to be the same John S. Karling, of whom Purdue University President Frederick L. Hovde was once heard to say, “responsible for reshaping and redirecting the biological efforts of Purdue [University].”

EARLY LIFE AND COLLEGIATE STUDIES

John Sidney Karling was the youngest child born to a large family outside of Austin, Texas. Plagued by ambiguity from the start, the exact year and location of his birth were uncertain among his family members, a fact which Karling attributed to the death of his mother shortly after his birth. However, early records place his birth on August 2nd, 1897. At the age of 16, Karling took the 20 entrance exams required to attend the University of Texas, but he passed only 12. Despite his performance, the school’s registrar allowed him to enroll, and Karling passed the remaining exams after matriculation. As Karling stated, “My entry into the academic field was purely by accident.”

During his time at the University of Texas, Karling considered studying law, medicine, or biology. In addition to joining what would later become the United States Army Air Corps, he was once invited to try out for the Chicago White Sox, alongside future Major League Baseball players Bibb Falk and Hall of Famer Ted Lyons. However, Karling’s talents resided in his studies, which he eventually focused on biology, and he received a master’s degree in 1920 for his work on latex production in plants.

In 1920, Karling began a Ph.D. program with botanist Robert A. Harper at Columbia University in New York. Karling obtained a Ph.D. in 1924, and continued at Columbia University as an instructor, assistant professor, and eventually succeeded Harper as Professor of Botany from 1927 to 1948. It was during his graduate work, focused on nuclear and cell division in green algae, that he became aware of microscopic, aquatic fungi that were parasitizing his algae samples. After preliminary study, he recognized that there was a wealth of biodiversity among the “Phycomycetes” (both uniflagellate and biflagellate "fungi") that was previously undocumented, which he was set to investigate. “By the time I had done that, I had become a mycologist, a student of fungi.” Thus Karling's expertise as a mycologist extraordinaire was due entirely to, “. . an accidental infection of the algae that I was studying for a doctor's thesis.”

"SIDE ISSUE TO MY TEACHING AND MICROBIOLOGICAL RESEARCH”

Karling’s academic responsibilities and pursuits at Columbia University were often pushed aside for various side projects. In 1925, Columbia University received funds from the Tropical Plant Research Foundation (of which Harper was the vice-president) and American chewing gum companies to study the production of chicle, a naturally occurring latex gum from the Mesoamerican sapodilla tree, Manilkara chicle. Karling was funded to take a six-month leave of absence every year, for nearly a decade, to travel to Belize (then British Honduras) and oversee the production of a 50,000-acre sapodilla plantation and research station. Within a year, Karling realized that a plantation model for chicle production was futile, because each tree required 50–75 years of growth before harvesting of chicle became cost effective. After Karling reported these findings, the American chewing gum companies encouraged him to continue his research regardless, while they further lined their pockets with the profits made from selling the highly marketable mahogany trees from the 50,000-acre land purchase.

During his surveys in Mesoamerica, Karling became increasingly interested in Maya archaeology. In December of 1931, after becoming lost during an expedition in Campeche, Mexico, he and botanist Cyrus Longworth Lundell of the Tropical Plant Research Foundation “accidentally found two rather large Maya cities, which had not been on the map at all, archaeologically.” This rediscovered area was named Calakmul by Lundell, his Maya translation of "City of the Two Adjacent Pyramids". For his part in the incidental rediscovery of Calakmul, Karling was awarded the title of Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1951. In 2002, the Ancient Maya City and Protected Tropical Forests of Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico was recognized as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Among his chicle work force of 290 Maya people, Karling was commonly, though mistakenly, regarded as a doctor of medicine. As he saw no harm in aiding with minor medical concerns, he conducted a clinic once a week, adorning himself with a white lab coat and displaying medical instruments to further the charade. Though his practice was mainly limited to administering malaria medicines or treating machete injuries, in one instance he aided in the delivery of twins, though he conceded, “I think I got more in the way than anything else.”

After his own afflictions with malaria, and the stagnation of chicle research, Karling sought to withdraw from Mesoamerica in 1937. However, based on his experiences in botany and tropical forests, in 1942 he was made field director of the United States government’s war-time exploratory surveys of rubber plants in the Amazon rainforest of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Frustrated by the monetary waste and the bureaucracy’s disinterest in the project, Karling left the post the following year.

"MY COMING TO PURDUE [UNIVERSITY] WAS ENTIRELY FORTUITOUS.”

During his tenure as Secretary for the Botanical Society of America (1945–1949), Karling was contacted by William L. Ayers, Head of the Department of Mathematics and Assistant Dean of the Graduate School at Purdue University, who asked if he was interested in applying for the recently-vacated Head of the Department of Biological Sciences. Karling declined, but suggested others he thought might be suitable for the role, though none were hired. Ayers persisted, asking Karling for consultation on the planning for the new life sciences building, now the Lilly Hall of Life Sciences. During multiple visits, he was hounded to take on the Department Head position by Ayers and eventually President Hovde. Karling finally relented, with the stipulation that the post be his for no longer than 10 years. Back at Columbia University, Karling visited the university president, future President of the United States, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, with whom Karling had several adversarial discourses. At the end of their last meeting, when asked by Eisenhower if there was anything he could do for him, Karling recounts: “I said, ‘No. I have just about decided to go to Purdue [University].’ [Eisenhower] said, ‘Fine. Why don’t you get the hell out of this big city and go.’” Karling believed that “this big city” had changed a lot during his 28 years at Columbia University, and he was ready to move on.

As Head of the Department of Biological Sciences beginning in 1948, Karling collaborated with other departments to (1) decrease faculty workloads by consolidating the curricula, which were needlessly repetitive between the departments, (2) revitalize the faculty and staff with new hires conducting research in the emerging fields of microbiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology, and (3) secure external funding for these research pursuits. In 1957 and 1958, Karling was also a visiting professor at the University of West Indies near Kingston, Jamaica. True to his word, on the 10-year anniversary of his hiring, Karling called President Hovde to tender his resignation. Hovde immediately sought a way to keep Karling at Purdue University, and through a large financial contribution in 1959, Karling was recognized as the John S. Wright Distinguished Professor of Biological Research, which would allow him to remain on staff, contributing his services and reputation to the University, while largely maintaining research independence.

Karling returned to international research and in 1963 was part of a UNESCO expedition of the Indian Ocean, with his role being to study the diseases of endemic fishes. The expedition’s lead vessel had previously been named the Williamsburg and had been the United States Presidential yacht, serving Harry S. Truman and Karling’s former Columbia University colleague, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower had the vessel decommissioned in 1962, and ownership was transferred to the National Science Foundation (NSF), which set about converting the leisure vessel to one repurposed for oceanographic research. Aboard the vessel, now the Anton Bruun to honor the Danish marine biologist, Karling found the vibrations of the diesel engines to be inconducive for microscopic work and instead worked on the mainland in India. During his return visits in 1964 and 1965, Karling was granted the title of C. V. Raman Nobel Laureate Visiting Professor at the University of Madras in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Additionally, in 1965 Karling secured NSF funding and a Fulbright Research Scholarship for two years to study fungi causing facial eczema in sheep and cattle in Australia and New Zealand.

KARLING/WHIFFEN VS. SPARROW: THE CLASSIFICATION CONFLICT

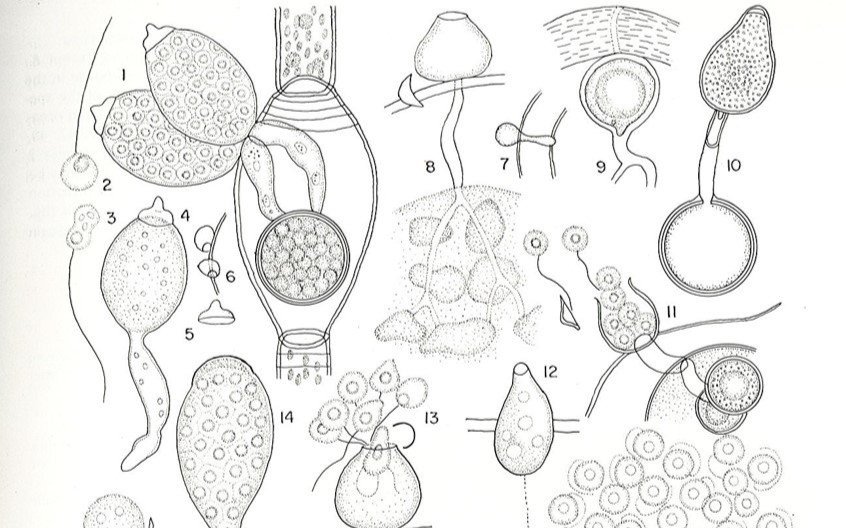

In 1943, Frederick K. Sparrow of the University of Michigan published the first edition of Aquatic Phycomycetes, a thorough monograph of zoosporic "fungi" (now recognized as members of the Chytridiomycota (chytrids or chytrid fungi, colloquially), Monoblepharidomycota, and Blastocladiomycota, and several biflagellate groups), detailing his system for their classification. Specifically, Sparrow believed that operculation, or the production of a lid-like cap over the pore through which mature zoospores exit the zoosporangium, was of the utmost importance when constructing the taxonomic framework for zoosporic fungi. In rebuttal to Sparrow’s system, in 1944 mycologist Alma J. Whiffen (later Whiffen-Barksdale) published her classification system, in which she de-emphasized operculation in favor of a system based on location of the developing zoosporangium, i.e., whether the nuclear material remained in the encysted zoospore (endogenous development), or the nuclear material migrated and a zoosporangium was produced elsewhere in the fungal thallus (exogenous development). Karling’s interpretation of aquatic fungi, instigated by his Ph.D. study of green algal parasites and perpetuated ever since, supported Whiffen’s theories, and he became a disciple of her classification system.

In the 2nd edition of Aquatic Phycomycetes in 1960, Sparrow conceded that his classification was an “admittedly somewhat artificial system”. However, rather than adapt to Whiffen’s proposal, Sparrow stated, “The writer does not accept [Whiffen’s] view, particularly since recent work has shown much variation in types of development within one fungus, whereas not a single authentic instance of a chytrid being both inoperculate and operculate has been recorded.” Karling was undeterred, and in 1977 he published his intricately illustrated work, Chytridiomycetarum Iconographia. Karling countered Sparrow’s assertion of the binary nature of operculation, citing over 30 years of research and observation supporting Whiffen’s rebuttal. Karling continued, “While the separation of the chytrids into the Inoperculatae and Operculatae may be convenient in classification, it is largely arbitrary, superficial, and not indicative of natural relationships, and for these reasons it is not recognized here.”

Both classifications of Sparrow and Whiffen have been widely contradicted by the hypotheses put forth by the advent of molecular phylogenetics in determining the fungal tree of life, in which operculation has arisen and been lost multiple times in disparate lineages. However, for students of zoosporic fungi, and those who, like Karling, accidentally become aware of “phycomycetes”, the publications by Sparrow and Karling serve as supplements to one another, with Sparrow’s thorough descriptions being brought to life by Karling’s ornate illustrations. Additionally, their decades of research on zoosporic fungi have made their names synonymous with the field. Indeed, honorific genera for both researchers (i.e., Karlingiella and Sparrowiella) have been recently described in manuscripts co-authored by chytridiomycologist D. Rabern Simmons, Curator of Fungi at the Purdue University Herbaria as of 2022.

FAMILIAL LIFE

Little is documented on Karling’s life beyond his academic travels and accomplishments. Karling married late in life in 1940, after having “just by accident” met Page Burwell Johnston, a secretary at Barnard College of Columbia University while visiting his summer cottage in Candlewood Lake, Connecticut. Their only child, daughter Sayre Christian Karling, was born in 1946 and graduated from West Lafayette High School and the University of Denver, Denver, Colorado. After marriage in 1967, Sayre moved to Chicago, but died at the age of 29 in 1976. Page lived in West Lafayette until her death in 2007 and was buried in Richmond, Virginia along with other Johnston family members.

LEGACY

Karling closed his lab at Purdue University in 1989. His published works of 180 manuscripts and 5 books span 61 years, from 1926 to 1987. In 1987, John and Page Karling attended the Mycological Society of America (MSA) meeting in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, for him to receive the MSA Distinguished Mycologist Award, the highest award bestowed by the Society, recognizing an outstanding career devoted to quality research and service to the field of mycology. After Karling’s death on June 3, 1995, his estate bequeathed $10,000 to the MSA. This donation was placed in an endowment fund and has continued to support the John S. Karling Annual Lecture, the keynote address of the Society’s annual meeting, making his name one of the most recognized in North American mycology.